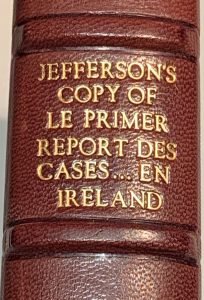

A BOOK ON IRISH LAW — FROM JEFFERSON’S LIBRARY

PURCHASED BY HIM IN 1775 FROM PEYTON RANDOLPH’S ESTATE,

AND ALMOST CERTAINLY REVIEWED BY HIM DURING HIS WRITING OF

THE DECLARATION OF INDEPENDENCE

JEFFERSON, THOMAS. (1743-1826). Third President of the United States (1801-1809) and author of the Declaration of Independence. Thomas Jefferson’s copy of Sir John Davies “Le Premier Report des Cases & Matters en Ley resolves adiudges en les Cours del Roy en Ireland, DUBLIN, Printed by John Franckton Printer to the Kings most excellent Maiestie. Anno.1615.” The first book on Irish case law, containing the reports of ten cases (nine in French and one in English) held during Davies’ term as Solicitor General of Ireland between 1604 and 1612. A 22-page preface is dedicated to Lord Thomas Egerton Ellesmere (c. 1540-1617), Solicitor General and favored adviser of Queen Elizabeth I. Contemporary calf, stamped in blind, raised bands. Spine rebacked and restored, else fine condition.

JEFFERSON’S MANUSCRIPT OWNERSHIP MARKINGS AT SIGNATURE “I” AND “T”

The book was primarily owned by Sir John Randolph (1693-1737), a legal scholar and a highly respected lawyer in Virginia. Known for his patience, integrity and concern for the rule of law, Randolph had an extensive library filled with legal volumes, with which he planned to write a history of the Laws of Virginia.

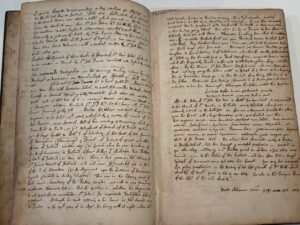

On the first four front blank pages Randolph has written a biographical note of the authors and signed his name.

These notes were taken from Anthony Woods’ Athenae Oxonienses. Athenae, which contained wide-ranging research on the city of Oxford and its citizens, was originally criticized for including the faults as well as the virtues of prominent people and places. Because of libel suits against him, Wood was expelled from Oxford University, and his book was publicly burned. Initial outcry against Athenae gradually turned into high praise, as Woods’ unparalleled biographical information proved invaluable.

Randolph’s library was passed on to his son, Peyton, upon his death in 1737. Peyton Randolph followed closely in his father’s footsteps, as Sir John had hoped, gaining the appointment of Attorney General of Virginia in 1744. After Peyton’s death in 1775, his cousin, Thomas Jefferson, bought the library that had been carefully amalgamated by two generations of Randolphs.

Thirteen years before his grand purchase of Peyton Randolph’s library, a young Jefferson left his studies at the College of William and Mary to pursue a career in law under George Wythe, a well-respected Virginia lawyer. After five years of tutelage with Wythe, Jefferson was admitted to the Virginia bar in 1767. Though a successful lawyer and member of the House of Burgesses, Jefferson never forgot his farming roots and spent much of his time running and caring for Shadwell, the family plantation. His time as a Burgess and his recognized literary abilities led him to become the author for the patriot cause in Virginia, and he was often called upon to help with the drafting of public papers. A scant year after the purchase of Peyton Randolph’s law library, Jefferson would draft his most important paper of all: The Declaration of Independence.

Jefferson took much pride in his vast library, often talking of it or citing certain volumes in letters to his friends, including James Madison and his former mentor, George Wythe. He would also lend books to contemporaries who asked for help understanding the law, and because of his generosity, those books sometimes “wandered” the country. For example, at the beginning of his second Presidential term, Jefferson lent the use of his law collection to William Waller Hening, clerk of the chancery court in Richmond, who had gained authorization to print the county’s statutes. When Jefferson retrieved his books from Hening at the completion of the project, he discovered an extra volume he had long believed was lost. Years before, when Jefferson had gone to France, he had lent the book to Peyton Randolph’s son, Edmund, who apparently forgot it belonged to Jefferson, and in turn, lent it to Hening. Hening eventually discovered the mistake and returned the book to its rightful owner.

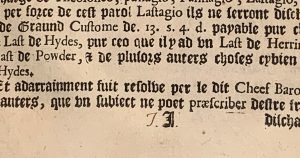

To mark his books as his own, Jefferson devised a clever way to use the printers’ signatures to identify them. To understand his method, it is necessary to understand the printing of books in Jefferson’s era differed greatly from the way they are printed today. Books were printed on large sheets of paper with a number of pages on each side, which were then folded in the proper format for the book: once for a folio (producing two leaves), twice for a quarto (four leaves), three times for an octavo (eight leaves), etc. The printer then identified each folded sheet, or gathering, with a letter of the alphabet, to tell the binder how the book should be put together. Most printers at that time used the 23-letter Latin alphabet (omitting the letters J, U and W), and printed the letters in the bottom margin of each gathering. These letters were called the printer’s “signature”. The binder simply arranged the gatherings in alphabetical order, and the book was finished. Jefferson, using the signatures to his own advantage, wrote a cursive letter “T” at the bottom of the “I” signature page (“I” being the Latin equivalent of “J”) and added a cursive letter “J” to the “T” signature page, with his initials “TJ” resulting in both cases. This clever phenomenon can be found on page 17 of the Davies book, which is the “I” signature page. The “T” signature page was removed at an unknown point in time, yet the wet ink imprint of the “J” remains on the verso of the opposite page!

In 1815, Jefferson sold his 6500-volume library to the U.S. government. It became the foundation for the newly rebuilt Library of Congress, the original having been destroyed by the British in the War of 1812. Because of it’s loan to Hening, this volume escaped inclusion in the Library of Congress purchase! When all his books were gone, Jefferson began a new collection, this time marking his volumes with block letters “T” and “J” instead of his previous cursive initials. A remarkable opportunity to acquire this piece of Americana. One of our: “The Best of the Best.”™

$87,500.00