AFTER DEFEATING THE BRITISH AT THE BATTLE OF PRINCETON,

GEORGE WASHINGTON

WORRIES ABOUT THE LOSS OF SUPPLIES AND THE LANDING OF THE ENEMY:

“IT IMPORTS US HIGHLY TO COLLECT A RESPECTABLE FORCE…FOR US TO SECURE…THE OBJECTS OF THE ENEMY’S ATTENTION”

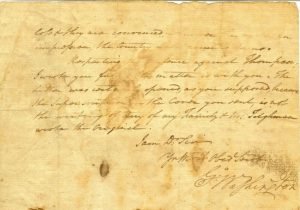

WASHINGTON, GEORGE. (1732-1799). First President of the United States (1789-1797). Important War-date Manuscript Letter Signed, “G. Washington”, as Commander of the Continental forces. Two pages, folio. Morristown, New Jersey, May 7, 1777. To [Brigadier] General [Samuel Holden] Parsons. Battle-worn and possibly bloodstained, but still in good / fine condition. [Call or email for details.] Washington writes:

“Dear Sir, I have been favored with your letter of the 2d inst., and am happy to hear the order for assembling men is likely to be attended with so great success. The loss of the flour at Danbury is to be regretted, but I cannot consider it in the important light you seem to do. Those at Derby are to be removed by a resolve of Congress and I hope the work is begun ere now having wrote Gen. G. McDougal and Clinton pressingly upon the subject. Such as are at New Haven and other places contiguous to the [Long Island] Sounds, should be removed as expeditiously as possible to some interior part of the country when they will not be liable to be destroyed on any sudden debarkation of the enemy. It would give me pleasure if the situation of our Army would justify the leaving of strong guards of Continental Troops at every place, subject to the landing of the Enemy, but as it will not, it imports us highly to collect a respectable force at such posts and passes, as are most important and material for us to secure, and which from their consequence, in all probability, are and will be the objects of the Enemy’s attention. I must therefore request that you will continue to forward on, all the hale and effective troops to Pecks Hill without loss of time. Such as are invalids or too weak to proceed yet from Inoculation or other Causes might remain, till they recover more strength, at the places where the Stores shall be removed to: they will serve as a guard and will aid in repelling any incursion the Enemy may attempt to make for their destruction. However I am inclined to believe they will pursue such measures with a great degree of caution. For tho’ they afforded themselves the stores at Danbury, yet it was with considerable loss and they are convinced whenever they make an impression, the Country will recur to arms. Respecting the sentence against Thompson, I wrote you fully and the matter is with you. The letter was certainly opened as you supposed, because the superscription on the cover you sent, is not the writing of any of my Family and Mr. Tilghman wrote the original. I am Dear Sir, your most obedient servant, G. Washington”.

In 1777, George Washington was General of the Continental Army, a position he had been appointed to two years earlier by the Continental Congress. Only five short months before writing this letter, Washington had turned the tide of the American Revolution by attacking and defeating German mercenaries employed by the British to occupy Trenton, New Jersey, on the Delaware River. The famous crossing of the Delaware on December 25, 1776, coupled with Washington’s promise to pay his troops out of his own pocket for extended enlistment, caused his army to double in size. He crossed the river for the second time on December 29 with 5,000 men, intending to force the British completely out of New Jersey. On January 2, Washington and his army were attacked by a regiment under General Charles Cornwallis, but used their retreat to their advantage by circling around the British troops and surprising three regiments that were on their way to reinforce Cornwallis. Moving through Princeton and eluding what was left of the British forces, Washington’s army secured a position in the hills of Morristown, New Jersey. From that vantage point, Washington attacked Cornwallis’s supply lines, and the British had no choice but to retreat into New York City, leaving only a small number of soldiers occupying a tiny corner of New Jersey. Washington spent the remainder of the winter fighting small skirmishes with the remaining British troops and, more importantly, actively recruiting more men for his own army. In this letter to General Samuel Parsons, Washington expressed his happiness “to hear the order for assembling men is likely to be attended with so great success.” Second only to his concern over recruitment, lack of provisions was one of Washington’s greatest worries throughout the war. In April of 1777, the British disembarked at Compo Beach, CT, raiding many nearby towns and destroying stores of food and supplies. In this missive, Washington expressed his hope that goods located along the Long Island Sound would quickly be moved so “they will not be liable to be destroyed on any sudden debarkation of the enemy out of access of enemy ships”. Washington’s concern was legitimate; he spent the following winter in Valley Forge, PA, where more than 2,500 of his men died from lack of food, clothing, shelter and medical supplies. Not letting the devastating winter crush his army or his spirits, Washington soon received the good news that the French had signed a treaty with the Americans to aid them in their fight for freedom. Washington, filled with renewed vigor, regrouped and proved to the French they could have faith in American soldiers. With France’s help, the colonies finally gained their freedom from Britain, and peace was officially declared on April 19, 1783.

Just an outstanding letter, written at an important junction of events in the American Revolution. Read it again, absorb the content, live the moment,…and then make it yours!

$58,500.00