DURING A LULL IN THE TRIPOLITAN WAR, PRESIDENT THOMAS JEFFERSON ASSURES MARYLAND CONGRESSMAN NICHOLSON THAT HE EXPECTS NO EXPANSION OF HOSTILITIES, AND IS THEREFORE REDUCING AMERICA’S NAVAL FORCE IN THE MEDITERRANEAN

“CERTAINLY NEITHER ECONOMY NOR PRUDENCE PERMITS TO KEEP IN ACTUAL SERVICE ALL THE FORCE WHICH MIGHT BE NECESSARY IN THE WORST STATE OF THINGS; FOR THEN WE OUGHT TO KEEP A LARGE STANDING ARMY…”

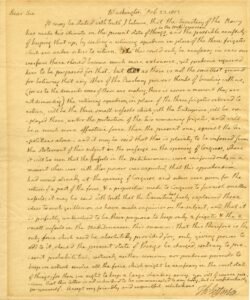

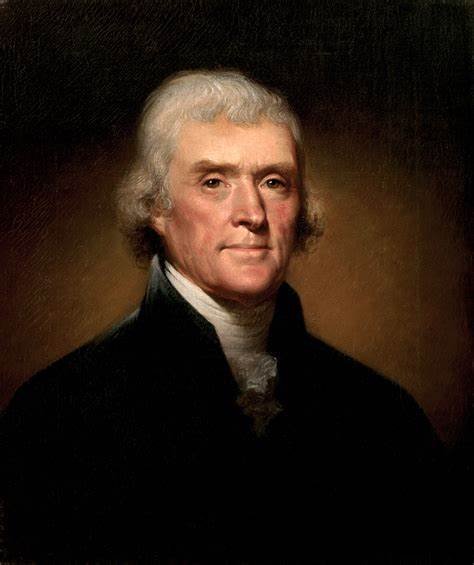

JEFFERSON, THOMAS. (1743-1826). 3rd President of the United States; and principal author of the Declaration of Independence. Important Autograph Letter Signed, as President, to Joseph H. Nicholson, noted politician and statesman from Maryland. Washington, D.C. February 23, 1803. One very full page, quarto. Jefferson writes:

”Dear Sir, It may be stated with truth, I believe, that the Secretary of the Navy has made his estimate on the present state of things in the Mediterranean, and the possible necessity of keeping that up, by sending a relieving squadron in place of the three frigates which are under orders to return. Tho this could only be necessary in case our warfare there should become much more extensive, yet prudence required him to be prepared for that. But as there is not the smallest ground for believing that any other of the Barbary powers thinks of breaking with us (for as to the demands some of them are making, there is never a moment they are not demanding), the relieving squadron, in place of the three frigates ordered to return, will be the three small vessels which, with the Enterprise, will be employed there, under the protection of the two remaining frigates, and will be a much more effective force than the present one, against the Tripolitans alone…and it may be said that this is plainly to be inferred from the statement of this subject in the message on the opening of Congress. There is will be seen that the vessels in the Mediterranean were reinforced only in a moment when war with other powers was expected, that this apprehension had ceased already at the opening of Congress, and orders were given for the return of a part of the force, & a proposition made to Congress to furnish smaller vessels: it may be said with truth that the Executive has freely explained these ideas to such gentlemen as have made enquiries on the subject, and that it is perfectly understood to be their purpose to keep only 2 frigates & the 4 small vessels in the Mediterranean this summer: That this therefore is the only force which need be absolutely provided for, only giving power to add to it, should the present state of things be changed, contrary to present probabilities. Certainly neither economy nor prudence permits to keep in actual service all the force which might be necessary in the worst state of things; for then we ought to keep a large standing army. You will of course perceive that this letter is not intended to be communicated to anybody, but is confidentially for yourself. Accept my friendly and respectful salutations Th. Jefferson”.

Congressman Nicholson, a Republican floor leader in the House, had written Jefferson the day before, alerting him to possible problems in passing “the Bill to reduce the Marine Corps” if it seemed that American forces would be stationed off North Africa for extended periods. Jefferson assures him he expects no expansion of hostilities, in spite of the bluster from the Barbary potentates. As Jefferson notes, this letter is in keeping with his message to Congress in which he told them that ships in the Mediterranean would be reinforced “only in a moment when war with other powers was expected.”

Diplomatic efforts with the corsairs of North Africa had commenced in 1795 when the United States signed a treaty with Algiers in order to insure safe passage of U.S. ships through the Mediterranean. Even after the Treaty of Algiers, piracy continued to be a major danger for American ships. The 1795 treaty provided the Dey of Algiers with a million dollars in ransom for American captives and promised an annual tribute. Although lessened, piracy was not eradicated.

When Jefferson became president in 1801, the Pasha of Tripoli demanded a new payment of $225,000. Jefferson refused, hoping to inaugurate a new era in Mediterranean diplomacy, but war broke out soon after. For two years, the United States Navy went unchallenged, with eight U.S. ships blockading Barbary ports and executing raids. By February 1803, Jefferson felt able to report to Nicholson that the conflict would be limited. He ordered three frigates homeward.

His optimism was misguided, however. In October, the Barbary Pirates seized the USS Philadelphia and its crew, and planned to use the ship to attack other American vessels. A year later the USS Intrepid was destroyed. In 1805, U.S. Marines executed a daring land raid on the Tripolitan city of Derna, memorialized in the “Marine Hymn.” The Philadelphia captives were ransomed for $60,000, treaties were signed and broken, and fighting continued intermittently until Commodore Stephen Decatur’s decisive victory in 1815, which finally ended the threat of the Barbary Pirates.

This letter also has great importance because it reveals Jefferson’s fear of another threat. In the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson condemned King George’s attempts to “render the military independent of and superior to the civil power.” After defeating John Adams and the Federalists in the electoral “revolution of 1800,” one of Jefferson’s first actions was to dismantle the Provisional Army authorized in 1798 during the war scare with France.

The crux of Jefferson’s argument, expressed here to Nicholson, is that the U.S. government could not afford to maintain “all the force which might be necessary in the worst state of things” in relation to the Barbary States, or to any foreign power. Like many of the revolutionary generation, Jefferson was committed to the positive ideal of the citizen militia turning out temporarily in cases of national emergency. He was, conversely, opposed to the idea of a permanent “standing army.” Jefferson saw standing armies as emblematic of oppressive European governments – they tended to bust budgets, produce a baneful influence in politics, and worse, to deprive citizens of their liberties.

Letters by Jefferson on the Barbary Pirates are of extreme rarity, and letters of this importance, and with this content make just a superb addition to any collection. One of our “Best of the Best”.™

$95,000.00