THE LIMITED EDITION OF THEODORE ROOSEVELT’S

THE WINNING OF THE WEST

CONTAINING A FABULOUS AND LENGTHY MANUSCRIPT PAGE, ALL IN ROOSEVELT’S HAND, ON THE ACTIONS AND CHARACTER OF GEORGE WASHINGTON IN HIS CAMPAIGN AGAINST THE NORTHWESTERN NATIVE AMERICAN INDIANS

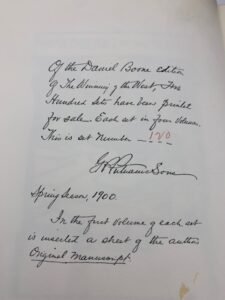

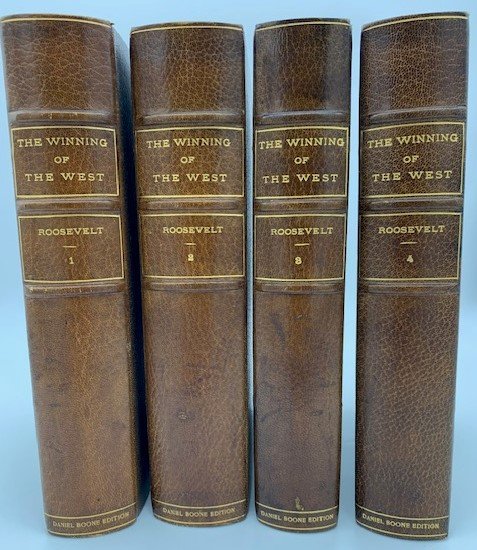

ROOSEVELT, THEODORE. (1858-1919). 26th President of the United States. The Daniel Boone Edition of his: The Winning of the West. First Edition. Set #120 of only 200 thus issued. G.P. Putnam’s Sons, New York, 1900. Four hefty volumes. Brown leather spines with gilt lettering. Extremely fine condition throughout. Illustrated with numerous plates and five folding maps. Tipped to front free end paper is the following Autograph Manuscript page, all in Roosevelt’s hand. It is an excerpt from the fourth volume of Roosevelt’s Winning of the West. He writes:

“of capacity as a general was so largely accountable. Washington and his administration were not free from blame. It was foolish to attempt a campaign against the Northwestern Indians with men who had only been trained for six months, and who were enlisted at the absurd price of two dollars a month. Moreover, there were needless delays in forwarding the troops to Fort Washington; and the commissary department was badly managed. Washington was not directly responsible for any of these shortcomings; he very wisely left to the Secretary of War, Knox, the immediate control of the whole matter, seeking ….

Tobias Lear, Washington’s Private Secretary as quoted by both Custis and Rush. The report of an eyewitness. See also Lodge’s “Washington,” p. 94. Denny, in his journal, merely mentions that he went at once to the Secretary of War’s office on the evening of the 19th, and does not speak of seeing Washington until the following morning. On the strength of this omission one or two of St. Clair’s apologists have striven to represent the whole account of Washington’s wrath as apocryphal; but the attempt is puerile; the relation comes from an eyewitness who had no possible motive to distort the facts. The Secretary of War, Knox, was certain to inform Washington of the disaster the very evening he heard of it; and whether he sent Denny, or another messenger, or went himself is unimportant. Lear might very well have been mistaken as to the messenger who brought the news; but he could not have been mistaken about Washington’s speech”.

By the time the final volume of Theodore Roosevelt’s The Winning of the West appeared in 1896 its author was widely recognized as a serious historian and a major national intellectual. For his history of the early frontier, Roosevelt drew upon the frontier thesis proposed by Frederick Jackson Turner at the Chicago World’s Fair in 1893, and retraced the ascendance of the American nation as the nation expanded ever westward. During the course of his research, Roosevelt came to see that stories of Native Americans abducting Anglo-American settlers occupied an important place in America’s early national literature. Roosevelt drew upon such abductions and their aftermath in a number of instances, as in “Mad Anthony Wayne: and the Fight at the Fallen Timbers,” the second chapter of volume 4 of The Winning of the West, where Roosevelt relates the story of the Miller brothers, William and Christopher.

While still young, the two boys were taken captive near their Kentucky home by the Shawnee. Raised as members of their abductors’ tribe, the two brothers parted ways when they reached maturity. At about 24 years of age, William, who had long wished to return to white society, did so; Christopher, who had grown to love his adoptive family, remained behind. The two separated, and William imagined he would never see his brother again.

In June of 1794, William Miller was serving as a scout under the command of General “Mad Anthony” Wayne when he was ordered to capture a Native warrior for interrogation. Accompanied by two other scouts, Miller came upon three Native Americans preparing a meal. The soldiers worked their way towards their prospective captive under the cover of heavy bush, and once within range fired upon two of the Natives. Both were killed. The third ran, leaping down a steep river bank into a muddy river. The scouts continued their pursuit, and the Native American, aware he was outnumbered and cornered, surrendered. Binding the limbs of their uncooperative captive for the return journey to Fort Greenville, the three men were shocked to discover that they had captured none other than William’s brother, Christopher. Brought back to camp as a prisoner, Christopher gave General Wayne the information he desired, and was offered a position as a scout and interpreter by General Wayne. Within days he joined his brother as a member of the scout detachment, where he distinguished himself.

Two months later, General Wayne led 3,000 soldiers against Native American warriors under the command of Blue Jacket, a Shawnee war chief. Blue Jacket’s army, about 1,500 strong, took a defensive stand along the Maumee River. The uprooted trees nearby provided the source of the battle’s historic moniker, The Battle of Fallen Timbers. Early in the battle, the Native army was outflanked by the American cavalry and began a hasty retreat. Falling back to the nearby British Fort Miamis the Native warriors found the gates barred. The commander of the fort, fearing possible reprisals from the pursing American forces, refused to give them shelter. After this victory, Christopher Miller served as the interpreter for the Shawnee during the negotiations which led the Native American tribes involved to accept the Treaty of Greenville. Through this treaty the United States gained control of much of present-day Ohio, paving the way for the creation of the state eight years later, and continuing America’s steady march to the Pacific Ocean.

A superb set, with the finest page of manuscript from TR’s pen that we have encountered. Simply, one of our: “Best of the Best!”™

$23,500.00