JOHN ADAMS

AN EXCEEDINGLY-RARE PRIVATEER’S COMMISSION SIGNED DURING THE UNDECLARED “QUASI-WAR” WITH FRANCE

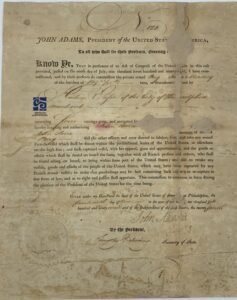

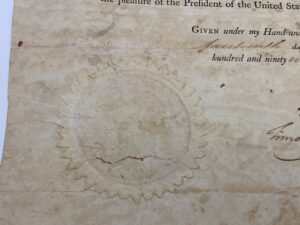

ADAMS, JOHN. (1735-1826). Second President of the United States; Signer of the Declaration of Independence; Vice President; and Minister to Holland and England. Exceedingly-rare Partly-Printed Document Signed, as President. One page, large folio. [approximately 16 x 13 inches]. Philadelphia, November 14, 1799. Countersigned by TIMOTHY PICKERING, Secretary of State. Large embossed white paper wafer Seal of State affixed with red wax at lower left. Professional archival repair to right center fold, and minor loss to two letters in Adam’s name, as seen in illustration accompanying this description, yet overall fine condition The rarity of this form of Presidential document, can not be understated. In our nearly 50 years of handling the finest of Presidential material, we have only offered one other like it, and by comparison, we have offered 5 William Henry Harrison’s documents signed as President. So, we are honored to be able to offer the following. It reads:

“JOHN ADAMS, President of the United Sta[tes of Ame]rica, To all who shall see these presents, Greeting: Know ye, That in pursuance of an Act of Congress of the United [S]tates in this case provide, passed on the ninth day of July, one thousand seven hundred and ninety-[e]ight, I have commissioned, and by these presents do commission the private armed Brig call[ed] Mercury of the burthen of 168 88/95 lbs tons, or thereabouts, owned by Ambrose Vasse of the City of Philadelphia merchant, mounting four carriage guns, and navigated by [….] herby licensing and authorizing John Ha[…] John Price [lieu]tenants of th[e] [sai]d Brig and the other officers are crew thereof to subdue, seize, and take any armed French vessel which shall be found within the jurisdictional limits of the United States, or elsewhere on the high seas; and such captured vessel, with her apparel, guns, and appurtenances, and the goods or effects which shall be found on board the same, together with all French person and others, who shall be found acting on board, to bring with some port of the United States, which may have been captured by any French armed vessel in order that proceedings may be had concerning such capture or re-capture in due form of lay, and as to right the and justice shall appertain This commission to continue in force during the pleasure of the President of the United States for the time being. Given under my hand and the Seal of the United States of Ame[rica] at Philadelphia, the fourth day of Novem[ber], In the year of our [Lord], one thousand seven hundred and ninety nine and of the Independence of the said States, the twenty fourth. — JOHN ADAMS By the President / Timothy Pickering Secretary of State”

With the signing of the Treaty of Paris in 1783, the American Revolutionary War came to an end, and official hostilities between the United States and Britain ceased. The new nation, seeking to create a stable economic base and hoping to leave war behind, allowed the U.S. Army to dwindle to only 700 men and sold the last remaining vessel of the Continental Navy, the frigate Alliance [in 1785]. Then, with the beginning of the French Revolution in 1793, British warships began interfering with American trade with France, and French warships with American trade with Great Britain. The continued seizure of American merchant vessels by French privateers, as well as the increasingly tense diplomatic relations between the two nations, led the U.S. Congress to pass a series of acts aimed at improving and expanding the small United States Navy. Among these defensive measures was “An Act to Further Protect the Commerce of the United States.” Passed on July 9, 1798, this act permitted President Adams to issue special commissions to private vessels. These private vessels were thus given the “license and authority for the subduing, seizing and capturing any armed French vessel, and for the recapture of the vessels, goods and effects of the people of the United States”.

Another area of genuine danger to American commerce came from corsairs of North Africa’s Barbary Coast. Raiders sailing from the ports of Morocco, Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis had made it necessary for European powers to either maintain naval squadrons in the Mediterranean or to pay annual tribute in order to assure their merchant vessels would not be interfered with. Prior to the American Revolution, American merchants in that region enjoyed the protection of the British government, but that protection evaporated with Independence. The combination of these events made clear the importance of establishing a U.S. Navy, and in 1794 construction was begun on the first six American frigates. This same year, John Jay, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, was sent to England to address American grievances with Britain stemming, in part, from the continued seizure of American ships. The result, Jay’s Treaty, improved relations between the two Anglo nations, but left France’s Revolutionary government, known as: “the Directory”, incensed.

Feeling that the broad definition of ‘contraband’ outlined in Jay’s Treaty violated the “free ships free goods” principle of their 1778 treaty with the U.S., France grew increasingly hostile. In 1795 alone, French vessels seized 316 American ships. Seizures, detrimental to the fledgling economy of the United States and an affront to its pride, were not the only source of tension between the two nations. When Charles Cotesworth Pinckney, the U.S. minister to France, arrived in Paris in 1796 the Directory not only refused to meet with him, but also drove him out of the city. President John Adams, seeking to avoid a war with the French powerhouse, sent a second delegation to France for continued negotiations. Arriving in Paris, these envoys were met by a French demand that the United States pay $250,000 if they wished to restore diplomatic relations between the two nations. When word of this reached America shores in 1798, President Adams informed Congress, and the event, known as the “XYZ Affair”, became international news. In the wake of this event, Congress rescinded the 1778 treaty with France and authorized U.S. vessels to capture armed French ships anywhere at sea.

The United States continued to rely on privateers throughout the Quasi-War as it’s maritime force expanded and Congress authorized the issuance of privateer contracts to supplement the newly created Navy. Over the next two years, American ships made prizes of approximately eighty-five French vessels, and the newly created U.S. Navy expanded to thirty ships. The aggressiveness of U.S. cruisers, coupled with the continued attacks on French vessels by the Royal Navy, finally forced France to adopt a more diplomatic stance toward America. Aggressive French maritime activity lessened dramatically, and in mid-December 1800 news reached American shores that the Quasi-War, America’s first armed conflict with a foreign nation, had ended with the signing of the Treaty of Mortefontaine on September 30.

Thus, we offer this simply superb, exceedingly-rare, piece of history!

$16,500.00